For many engineers, when you say parallel compression they immediately think of drums or bass and never think about doing parallel compression on a vocal.

This is a useful technique but it’s often poorly executed by beginner and intermediate engineers.

I usually use parallel compression if I’m working on a bad recording or when a vocal is struggling to cut through a dense mix.

In some cases, I might use the technique to keep the original vocal dynamic. But most frequently the technique is used to solve problems.

In some cases just to add attitude, warmth, and character to the vocals.

We’ll get into that later on, let’s first get into one of the frequently asked questions about vocal parallel compression.

Is Parallel Compression Necessary on Vocals?

Instead of squashing the transient on the original vocal track in order for the quieter parts to be more audible, parallel compression allows you to squash the parallel track to make the entire vocal constant in volume.

So, YES, parallel vocal compression is necessary on a voice to make sure that every word and consonant is audible.

It will help the vocal cut through, keep the musicians happy, and make sure that the mix translates well on different sound devices.

The technique can also be used if you have a bad recording.

You may find yourself in a situation whereby if you compress the vocal it starts bringing up unwanted frequencies, breaths, and background noise.

In that case, you can compress the parallel channel as much as you want then blend it with the original signal for a better sound.

The benefit of a parallel track on a vocal is that it will make the vocal seem more up-front.

The goal is never to make it sound obvious though, it’s supposed to be felt instead of being heard.

This means you’ll definitely notice when the parallel track is muted.

However, once it’s in you’ll feel the difference more than you hear it.

Later on, I'll show you a more advanced technique that you can use to add, attitude, warmth, and character to your vocals using parallel compression.

Now, let’s get into the technical part of things.

Parallel Compression Settings

One thing that will make you struggle with the parallel compression settings is if you have no intent or a valid reason as to why you need to apply parallel compression.

If you know what you want to achieve with the parallel track then the settings will be much easier to figure out.

For instance, if you want to add punch to the vocal you use a slow attack.

If you want to bring up the sustain then a medium to slow release will do the job.

If you want the vocal to sound smoother then a fast attack with a medium release will keep the vocal smooth and well-controlled.

So, it really depends on your intention.

You have to picture the final results even before you think about which compressor you’re going to use.

Parallel compression can be useful for many different reasons that’s why I can’t recommend any specific settings.

Listen to the source, determine what it needs, and then come up with settings that will help you achieve your goal.

One thing I would strongly recommend is to compress the signal hard enough to get the entire vocal consistent in volume.

You don’t want to have the parallel track sounding too dynamic, that just defeats the purpose.

And then play around with high and low ratio settings till you find what works best for that particular vocal.

High ratio settings can work well when you want to control loud peaks or a vocal that's too dynamic.

Low ratio settings usually work well if you're not going for control but to shape the envelope.

Obviously, these rules can be broken, however, it's a good starting point.

Take Advantage of Doubles

Some recording engineers will have multiple takes or doubles of the lead vocal.

You can take advantage of those instead of creating a parallel track.

You can heavily process the vocal doubles and leave the original lead vocal with minimal processing.

So, you’ll use the double to make sure that the vocal cuts through and that every syllable is audible throughout the entire song.

This technique works well when you’re working on a dense mix or if you’re mixing a bad vocal recording.

Just like parallel processing, blend the vocal double(s) so that they’re more felt than heard.

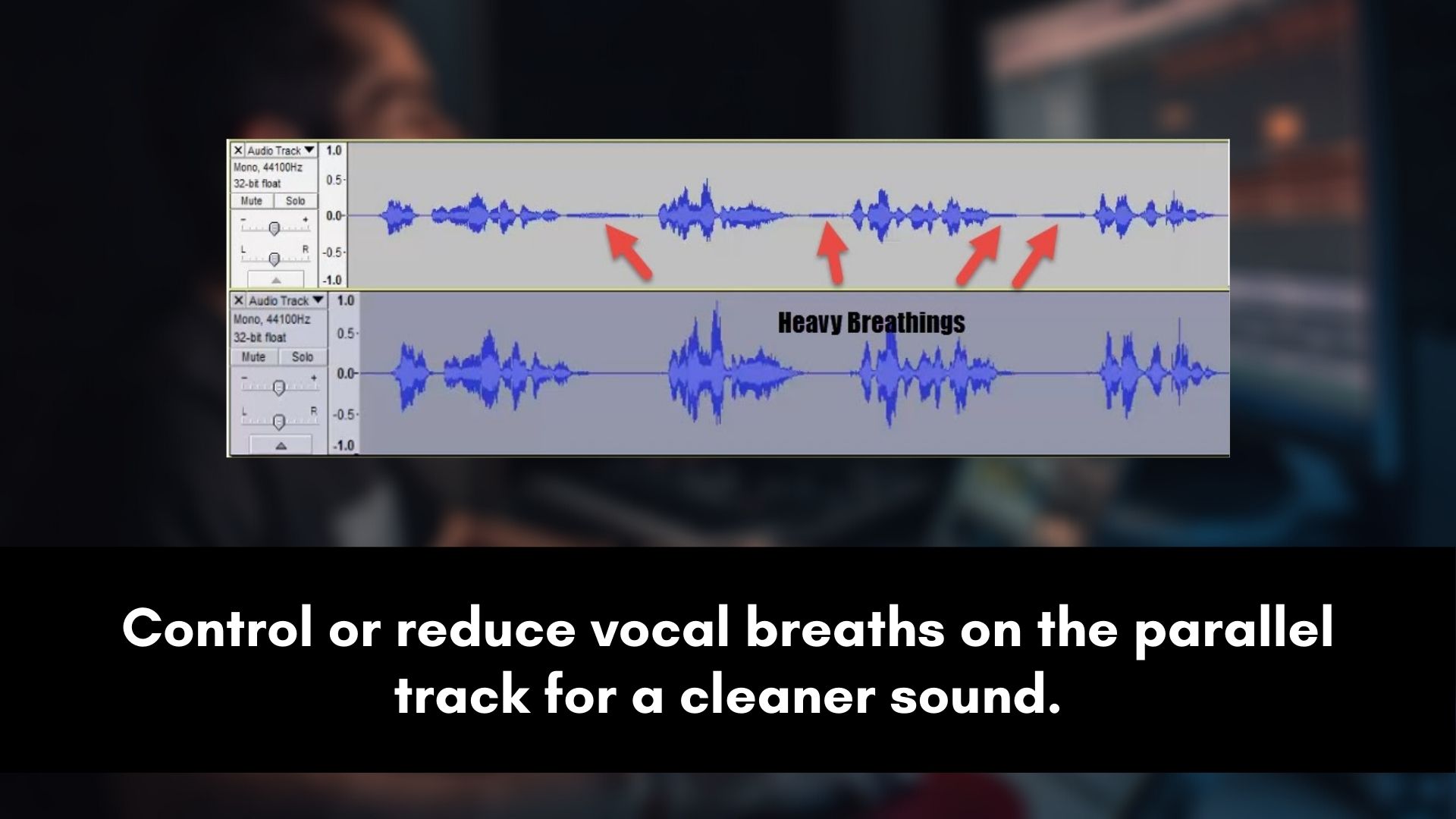

Control Vocal Breaths

When you’re doing vocal parallel compression, the loudest peaks will be squashed and the quieter parts will be increased in volume.

This will also bring up vocal breaths, and in most cases, they’ll be annoyingly way too loud.

You may need to bring down those vocal breaths for a better and cleaner sound.

You can manually bring them down by automating the clip gain (pre-gain) or use tools such as the iZotope Breath Control plugin.

This will help you reduce or remove distracting breaths between words and phrases.

There are other companies such as Waves Audio who also produce great plugins that’ll help you control vocal breaths.

You’ll also need to do some manual gain automation because I’ve realized that these plugins do miss some of the breaths.

You can choose to remove them completely or reduce them, that’s just a matter of taste.

Just make sure that they’re not too loud to a point where they annoy or distract the listener from enjoying the song.

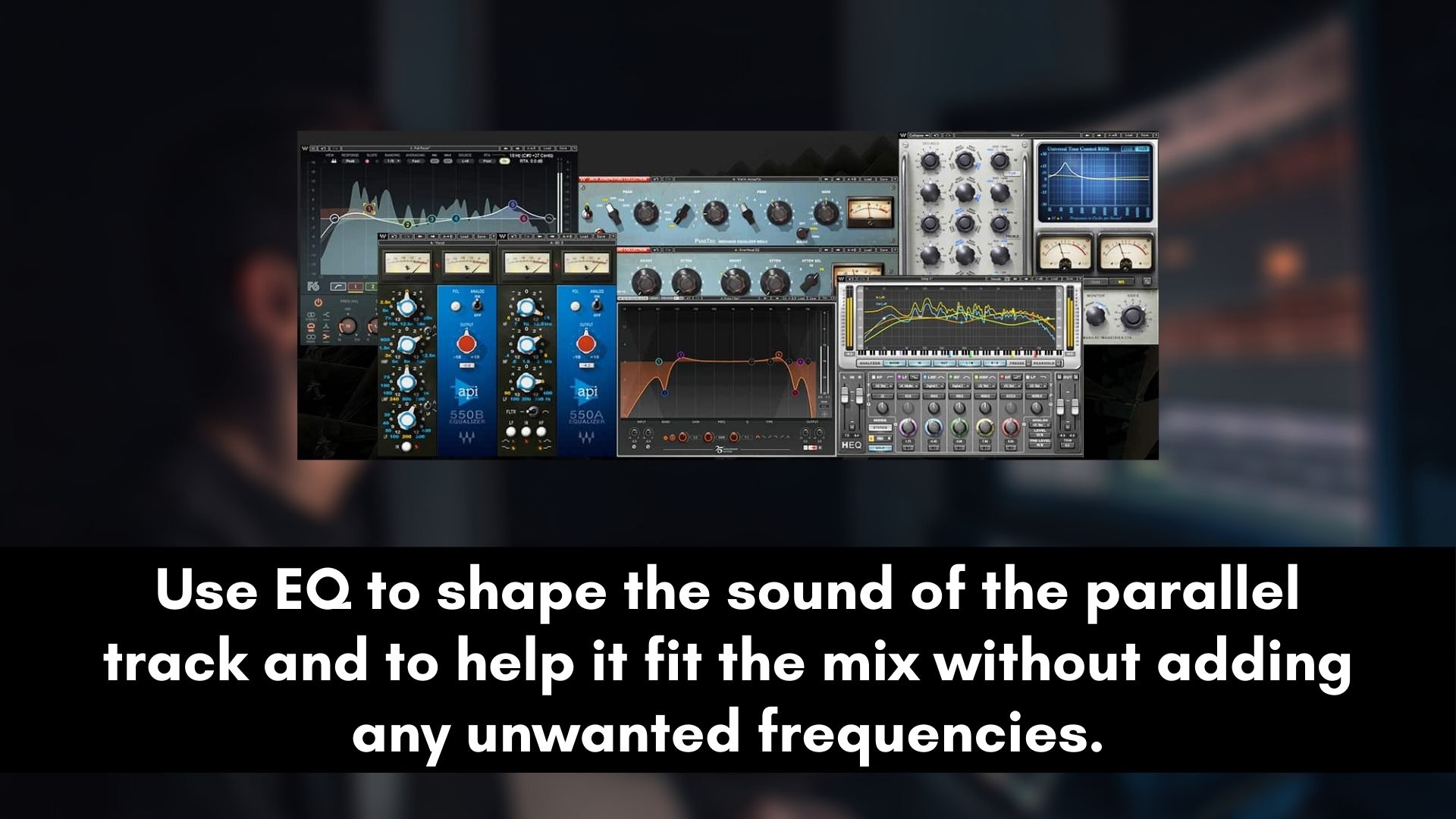

EQ The Parallel Track

Another issue about parallel compression on a vocal is that it can sometimes amplify problem frequencies.

It may bring up the room sound, mud, harshness, or any other unwanted frequencies.

In some cases, you might need to use an EQ to reduce problem frequencies.

While in other situations you’ll need to boost certain frequencies to help the vocal to become present in the mix.

You may also find that the vocal is sounding too thin so you’ll need to boost frequencies to add some warmth to the vocals.

This happens mostly on a female vocal.

A boost in the bass frequencies (80Hz to 200Hz) will make the vocal sound warmer and thick.

Just make sure that you don’t bring up any rumble or sub frequencies (80Hz and below) that can usually cause more problems and create clutter in the low-end.

So, use EQ to help the parallel vocal track fit the mix without messing up the clarity of the mix or bring up any unwanted frequencies.

It is also wise to use a linear phase EQ to avoid adding any phase distortion.

De-Ess The Parallel Vocal

As I’ve already mentioned above, hard compression will bring up some unwanted stuff such as background noise, breaths, etc.

One other problem with hard compression is that it may bring up vocal sibilance and harsh frequencies.

Sibilance is piercing frequencies caused by consonants such as S, F, SH, Z, C, and X.

If these are not well-controlled they’ll make the vocal sound harsh and piercing.

These are also called “esses”, that’s why the tool to control them is called a de-esser.

Obvious, right?

De-essing is the method or process used to reduce or control these harsh sounds.

You can reduce them by manually automating the clip gain on the parallel track or by simply using a de-esser plugin.

If you choose to use a de-esser plugin, at least manually automate the de-esser settings to make sure that the plugin catches all these “esses”.

Remember, a de-esser is a tool, so it can never be 100% accurate.

If you’re lazy or maybe working with a client that’s in a rush then use 2 different de-esser plugins.

Let one de-esser take care of all the frequencies between 2kHz to 5kHz, then let the other de-esser take care of the frequencies between 5kHz to 10kHz.

That way you’ll be able to catch all the different sibilance.

Multi Parallel Compression On Vocals

Most of the time you’ll reach for an EQ to make things brighter or darker.

However, that’s not always the right approach.

Putting the signal into some circuitry will affect the signal in a much more natural and musical way.

I call this multi parallel compression on a vocal because I don’t have a name for it, and the people who taught me this trick never mentioned its name.

This is more of an advanced trick so you’ll need to know your way around a compressor.

In order to do this, the dynamics on the original vocal track will need to be well-controlled.

You’ll also need to do other processing needed to get the vocal sitting well in a mix.

We’ll be using multiple compressors for tone and attitude.

This is not so much about the compression, but the sound of these compressors and giving your vocals attitude.

For instance, if the vocal is horribly recorded you might not want to rely too much on eq to get a certain sound but the tone, circuitry, and transformers of analog compressors.

So, you’ll need to get a bunch of tube compressors for this technique to sound awesome.

Using transparent compressors is really pointless.

The thing about tube compressors, aka Vari-Mu, is that they add certain color and sonic characteristics to a sound.

The circuitry of these compressors add color, and when put together they give presents and add warmth to a vocal.

To do this, you’ll need to create 5 Aux/Fx channels, add 5 different compressors on each aux channel (preferably analog emulation compressor plugins), then send each aux track to the lead vocal.

Compress to taste, without squashing the signal of course.

Then bring the volume to -inf (zero) and then blend to taste.

The good thing about tube compressors is that each has a certain sound, some add more midrange, others sound bright, while some are dark, etc.

So you blend them based on what the vocal needs the most.

Check out the video below to get a visual representation of this strategy and listen to how it affects the vocal in such an amazing way.

Parallel Compression on a Vocal

Wrap

Vocal parallel compression involves minimally processing the main vocal and applying a more obvious amount of compression to the same source on a parallel track or double(s).

It also works if you’re mixing a bad recording and don’t want to do too much processing on the main vocal, or when you’re mixing music that needs a minimal amount of compression.

When necessary, use tools such as de-esser, eq, de-noise, gates, expanders, auto-tune, etc. to clean the parallel track.

One of the biggest mistakes you need to avoid is sending all vocals to the parallel track, only do it on the lead, not on the supporting vocals.

Another mistake you don’t want to make is not compressing enough.

The goal of parallel compression is to get the loudest peaks at the same volume as the quieter parts of the vocal.

So, you’ll need to apply some hard compression.

Usually nothing less than -10dB of gain reduction.

Parallel compression on a vocal is a great technique but you should always do it with good intention.

Not all vocal recordings will need parallel compression.

Finally, don’t think that parallel compression is good for drums or bass only.

Now is your turn to try parallel compression on a vocal.

Leave a comment below to let me know if you’ve ever done it on a vocal, and if you haven’t then at least let me know that you’re excited to try it out.